There’s something about the first dog that finds you… that lives in your heart the longest.

“Wanna dog?” asked the driver of the white, enclosed box truck that picked me up hitchhiking.

“A what?”

“Yeah, got a truckload of ’em in the back,” he said, stopping to let me out at my car.

I had just finished kayaking the Tuolumne on my day off from guiding and had another two weeks of work in California before returning home. A year out of college, I was still living at my parents’ place in upstate New York.

“Not really,” I said, unsure what he meant.

“Too bad. I’m heading to the research center down in Sac. You’re not from around here, are you? Animal control in Tuolumne County’s basically a kill shelter. When they run out of space, they ship them out for research.”

I grew up with dogs, from Labs to Scotties. Loved the Labs; the Scotties, not as much; they were always biting ankles they didn’t recognize, and occasionally mine.

He led me to the back of the truck and swung open the large door. Havoc broke loose. There were a dozen dogs, all sizes and shapes, stacked in separate cages, barking excitedly… all but a small black and tan one. It sat up in the cage and tilted its head to the side.

“I really have no place to keep it,” I said, guilt tugging at my gut. “O.K. that one.”

“Great,” he said, taking the little black and tan one out. “One less on my conscience. Possibly a beagle mix or something? Yeah, except the feet are big enough to trip over. Looks like a girl,” he added, examining it underneath and handing it to me.

She was shaking.

“Here, you can use this,” he said, unfastening his belt, threading it through the buckle, and cinching it around the dog’s neck. “This job sucks, can’t even tell my kids what I do, but it pays the bills.” He climbed back in the truck and called out the window, “Whatever you do with it, I guarantee it’s better than where it was headed.”

I wasn’t so sure. When I wasn’t on the river, I was living in the company’s guide trailer. The toilet didn’t flush, the sink was clogged with last year’s dishes, and there was no air conditioning. When I got back to the trailer, one of my fellow guides asked,

“Eric, what are you going to do with it?”

“I was thinking I could tie it under a tree with food and water.”

“For three days at a time?”

“Better than that hell-hole of a trailer.”

The temperature in Sonora often exceeded 100 degrees, and without shade, the trailer was an oven. The occasional scrub oak tree, hunched over the parched yellow hay, offered the only respite from the cloudless summer.

I placed a folded blanket under an oak, along with large bowls of dry dog food and water, and tied her up. She just sat there, looked at me, and cocked her head. That head tilt would become a regular thing between us.

I wasn’t sure what I’d find when I returned after my trip. She’d be easy prey for a coyote, and if she chewed through the rope she might wind up back in that truck heading for Sacramento.

The three days on the river dragged on, to the point where I was having trouble concentrating on the clients and the rapids.

When I got back, I skipped breaking down the trip gear and went straight up to the tree. She was lying on the blanket. When she saw me, she sat up and wagged her tail and cocked her head to the side. I picked her up, and she licked my face.

For two weeks, she endured beneath the oak tree. I still hadn’t heard her bark.

When I put her in a crate at the San Francisco Airport to fly home, I imagined she thought she was being abandoned again.

Our property in upstate New York bordered a large state park. There she flourished on hikes and bike rides, and started to grow into her feet. Within a couple of months, she was twice the size of a beagle. She never needed crate training, instinctively knowing to go outside.

I brought her to a vet who had no idea what she was, other than that she was female, approximately four months old, and without a shred of beagle.

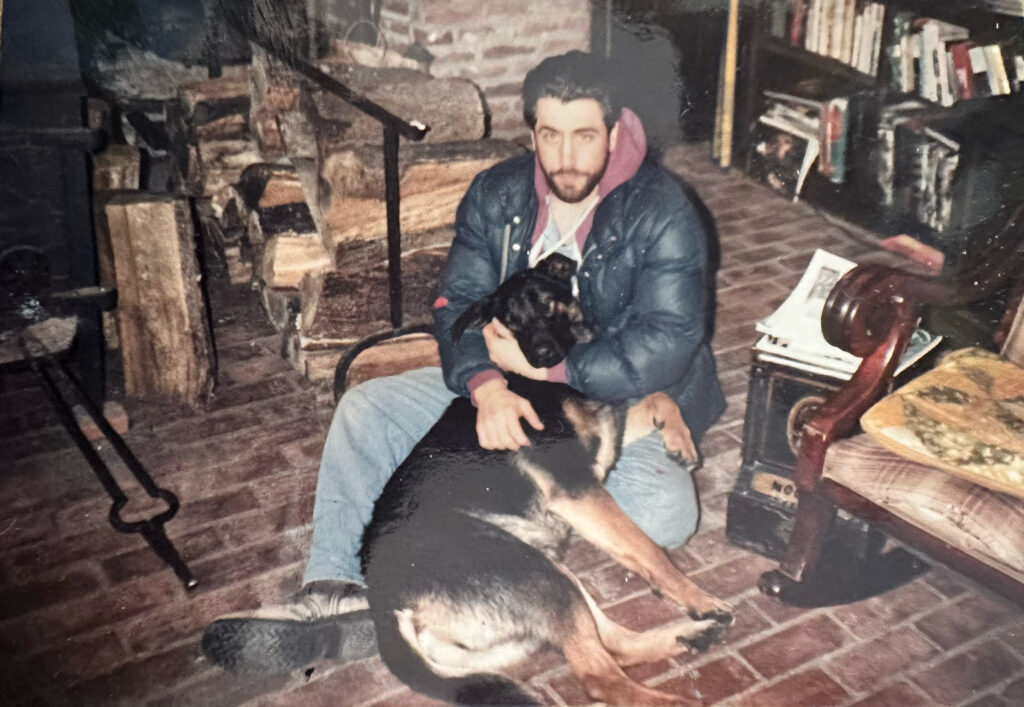

I named her Tuolumne, after the river I worked on that was threatened by a dam. She was mostly black, with a tan chest band and tan legs. When she heard something, her ears would stand up like a German Shepherd’s; otherwise, they sat in a compromised, halfway-up salute, with the top flaps sticking out at 90 degrees like miniature wings. Over the year, she grew to 75 pounds, could run for miles, and effortlessly jump into the back of my pickup truck.

The following summer, I left her with my parents for a couple of months when I headed back to the Tuolumne to work.

I was getting gas at a Circle K in Sonora when a dog fetching a ball in the fenced yard next door caught my eye. It had the same powerful build, coloring, and athleticism as Tuolumne, only larger. It even had the same comical, 90-degree floppy ears.

“Mind if I ask what kind of dog?” I asked the owner, while the dog sat there, shaking with excitement, waiting for the ball to be tossed.

“Doberman Shepherd mutt,” he responded, throwing the ball. “Best dog I ever owned. He’s smart and a hell of a watchdog. Would you break into a house with this 90-pound monster? Great with my kids, too.”

“How old?” I asked, already positive it was Tuoloumne’s brother.

“Around a year, the vet thinks. Picked ’im up at Animal Control last June. They told me a champion Doberman got loose and knocked up some lady’s German Shepherd. There were eleven of them in the litter. She got rid of six; the last five ended up at the shelter. I grabbed this guy. A friend wanted one, too, but the only one left was the runt, and besides, he wanted a male. God only knows what happened to it.”

A similar story would repeat itself a generation later, on another continent, with my son, Cade.

Cade was kayaking near Puerto Varas, Chile, and staying at a small campground. Each evening, a fuzzy black-and-tan puppy, the size of a large house cat, would emerge from a nearby swamp, steal the cat food the manager had left out, come over to Cade’s campsite for a visit, and then disappear back into the swamp for the night.

Cade woke up the third morning to find the puppy peacefully curled up under his van. He asked the campground manager about it. The manager lamented that he was sick and tired of the dog stealing the cat food and urged Cade to take the dog. The cats had a job, keeping the mice at bay, but the dog had none.

Years earlier, municipalities in Chile had abandoned dog shelters in favor of a laissez-faire system, where abandoned dogs were left to fend for themselves on the streets or wherever else they were dumped. In downtown Puerto Varas, where Earth River guests spend their first night, there’s a pack of friendly, surprisingly healthy, mixed-breed dogs of all shapes, sizes, and ages that survive on handouts. In rural areas, it’s bleaker. The only dogs that survive are those that turn wild and hunt native species like the highly endangered pudú, the world’s smallest deer, standing just two feet tall.

The farm in the Futaleufú Valley, where Earth River’s guide house is located, also serves as a campground for kayakers called Cara del Indio. It is owned by the Toros, one of the original colonizing families. Cade was concerned about how the dog would fare if left alone with the farm animals, especially the ducks and chickens. In rural Patagonia, dogs that attack farm animals often end up in the river.

Cade decided the dog had a better chance at the farm than being left to fend for itself, especially if the cat food was cut off. After confirming the puppy’s abandoned status with some neighbors, he left with it. The dog had no idea it would spend the rest of its life commuting between Patagonia and New York.

He named him Osito (“Little Bear”), which was exactly what he looked like after a couple of months of receiving barbecue handouts from camping kayakers on the Futaleufú. Luckily, he was a quick study, requiring just one unfortunate duck, and some intense scolding, to get the message. In just a few short months, he went from being the cat food bandito to Earth River’s First Gentleman.

When Osito was crated for the flight to New York after the Futaleufú season, he didn’t cry or bark. Thirteen hours later, when Cade let him out, he just wagged his tail.

Back in New York, Osito doubled in size and grew into an Australian Shepherd of sorts. In Patagonia, dogs are born, not bred.

Earth River’s Futaleufu Mascot

Osito greets all Earth River guests when they arrive in the Futaleufú Valley with a vigorous tail wag that involves his entire back half. He often joins Earth River groups on the hike to Lago Obsession and in one of the small raft we take on the Espolon and Azul rivers.

He’s almost too friendly. During the first month back in New York, Cade took him rafting. While the boats were being inflated, Osito went missing. After a short, frantic search, Cade found him happily sitting in the passenger seat of a stranger’s car.

Over the past few years, Osito has made many friends on our Futaleufú trips. With boundless energy, he plays with any willing partner, on two legs or four. For Earth River guests who miss the four-legged companions they left at home, and even for those who didn’t, he’s a great ambassador and a welcome addition to the Earth River team.