With some trepidation, I watched the original Terminator Rapid video, which marked the end of the first attempt to raft the Futaleufú. Like a giant yellow beach ball, one of the fully loaded 22-foot rafts was swept into the center of the river, where it slammed into a recirculating wall of water and came to a violent halt, thrashing and spinning for 30 minutes before finally being let go. Stripped down to the tubes, the limp raft floated helplessly downstream.

The rapid, aptly named Terminator, marked the end of Steve Currey’s 1985 attempt to raft the wild Patagonian river with the melodious name few had heard of and even fewer could pronounce. While Steve’s Provo, Utah-based company, Currey Expeditions, had successfully navigated the upper river and nearly a dozen rapids, the lower half—including the now-renowned Bridge-to-Bridge day-trip stretch and another 14 significant rapids, remained an enigma to the rafting community for the next five years.

The month before I watched Steve’s Terminator video, I was in Northern Patagonia scouting the same “unraftable” river. I marveled at the swirling turquoise water from a bridge, where a sign read, ‘Futaleufú, un paisaje pintado por Dios’ (‘A landscape painted by God’). The road sign’s message intrigued me and further piqued my imagination. As I drove up the road, I was amazed by the valley’s stunning beauty. The road followed the river for the first few miles, and I stopped multiple times to examine different rapids. They looked daunting, but I could see possible routes through them and decided to launch an exploratory trip the following February.

Planning Earth River’s first descent

When I returned to the US, I contacted Steve Currey about my plans. He was extremely pessimistic:

“Eric, forget it. It’s a waste of time. If the river had any commercial promise, I would have returned.”

He explained that their fully loaded, 22-foot, self-bailing rafts were an advantage when breaking through the giant waves in the constricted upper canyon, but they required Herculean strength to control in the rocky, technical rapids of the lower section, such as Terminator. I invited Steve to join the expedition, but he declined and sent me a video from his trip that included the Terminator debacle. “Watch the video,” he said, “and see if you’re still interested.”

Image: Terminator Rapid

Image: Terminator Rapid

Terminator incident

There were four rafts on their attempt, rowed by an experienced team consisting of Steve Currey (trip leader), Peter Fox, Dan Bolster, and Brad Lord. The fully loaded oar boats had people holding on and looked more like something you’d see in the Grand Canyon. The grainy video and dark, gloomy weather gave the river an ominous feeling. In Terminator, Brad’s boat was slightly offline and surfed out to the center, where it slammed into a giant wave of recirculating water and was thrashed for what seemed like an eternity. I couldn’t tell from the video but apparently everyone was rescued. As daunting as Terminator appeared, I was undeterred. With light, maneuverable boats and trained client paddlers assisting the oarsmen, I thought it might be possible to run commercial trips. Seeing the entire river was the only way to know.

In early February of 1990, Earth River launched an exploratory trip on the Futaleufú with two oar-paddle-assisted rafts, guided by Randy Michaels and me. Chris Spelius, whose company Expediciones Chile had been offering expert kayakers trips down the river for a few years, was the lead safety kayaker. Each raft had four paddlers, consisting of intrepid paying clients and training guides. Baggage was kept to a bare minimum. At the last minute, Steve Currey decided to fly down and join the expedition, but because of back issues, he would only be part of the land team.

While we were scouting the first major rapid in Inferno Canyon, Chris mentioned that he was curious to see how the rafts would handle the bigger rapids of the ‘Futa.’ He had his doubts, as did other outfitters at the time. Having kayakers along who were familiar with the river proved to be an advantage. Even so, rafts and kayaks often take different routes, and Randy and I spent hours scouting rapids. The rafts made it through Inferno Canyon and down to unnavigable Zeta Rapid without any incidents. Zeta was a mandatory portage—the entire river squeezed through a dangerous, undercut, Z-shaped slot.

Image: Put in (start) first raft Descent. (Earth River’s 1990 brochure cover)

Image: Put in (start) first raft Descent. (Earth River’s 1990 brochure cover)

Portaging can be more dangerous than running rapids

Randy and I decided to “Ghost Boat” the rafts, carry the gear around and push the empty rafts through. One raft made it to the bottom, but the other flipped and got stuck in a carved-out pocket in the right wall. If the boat could not be freed, the expedition would end there. Steve had mentioned a similar incident during his 1985 expedition. He told me that they took so long to circumvent the rapids that they were forced to camp there.

Image: Zeta Rapid (Boat was stuck in the indentation below bare rock on river right.)

Image: Zeta Rapid (Boat was stuck in the indentation below bare rock on river right.)

With the aid of ropes, Chris and I climbed down the 50-foot wall and jumped on top of the bobbing, upside-down raft. The plan was to flip the boat back over and row it out of the eddy. We attached a flip line to the side and stood on the edge, ready to pull the upside-down boat back over, when I noticed the water below disappearing under the wall and reemerging 30 feet downstream. Ending up in the water after the boat flipped over and getting sucked under the wall was committing suicide. I alerted Chris to the water flowing under the wall, and the plan was aborted. Two hours later, we finally freed the raft by attaching a throw rope to the bow and tossing it to Randy on the opposite shore, who then pulled it out.

With the exception of a near-flipped raft that dumped everyone but Randy out in a nondescript rapid we named ‘Asleep at the Wheel,’ the rest of the upper river down to the infamous Terminator Rapid, went smoothly. Below Terminator, we successfully negotiated over a dozen major rapids, including: Mundaca, Más o Menos, Casa Piedra, and I was convinced of the river’s commercial potential.

Note: I’ve never heard of another raft getting stuck in the middle of Terminator Rapid, like the incident that cut short Steve Currey’s first attempt 40 years ago, most likely because today’s boats are lighter without gear, and paddlers now assist the oarsman.

Image: Author guiding in Chile, circa 1990

Image: Author guiding in Chile, circa 1990

The following January (1991), we returned to the Futaleufú with commercial groups. In 1992, we installed a water gauge to establish high-water safety cut-offs. Bio Bio Expeditions scouted the river in 1993 and began offering commercial trips. Then, in 1994, we introduced a major safety innovation to the river: the ‘Safety Cataraft.’

From obscurity to one of the top rafting destinations in the world.

There are now nearly a dozen rafting companies operating on the Futaleufú. The majority are local Chilean companies running the world-famous “Bridge to Bridge” day-trip section, which Earth River rafted first and pioneered in 1990 and which accounts for 99% of the river’s rafting traffic. Rafting is the largest industry in the area, and the publicity generated by the river has been the most important deterrent to mines and dams.

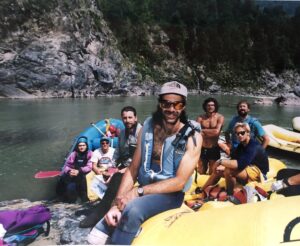

Image: Futaleufu first descent rafting guides: Randy Michaels (center foreground) & Eric Hertz (behind left)

Image: Futaleufu first descent rafting guides: Randy Michaels (center foreground) & Eric Hertz (behind left)

A world-class rafting and multi-sport adventure.

With more than three and a half decades of experience on the Futaleufú, Earth River now offers multi-day rafting, biking, inflatable kayaking, and hiking multi-sport adventures in the valley ‘painted by the hand of God.’ Our lodge-based trips blend comfort with chef-prepared meals and are suitable for people of all ages and abilities.

Historical Note:

A misnomer about the exploration of the Futaleufu

The Biobío River in Chile was one of the great rafting rivers in the world until it was dammed in 1993. It’s often misstated that the Futaleufú was scouted as a replacement for the imperiled Biobío. Steve Currey told me he first saw the Futaleufú as a teenager on a Mormon mission in 1970, nearly a decade before the Bio bio River was ever even run, and two and a half decades before the dams on the Biobio were proposed. In 1985, 5 years before the Chilean Congress approved the Bio bio dams, Steve fulfilled his ambition and returned to run the Futaleufú.

My impetus for taking another look at the Futaleufú in 1990 was solely to find another destination for our guests. At the time, the dams on the Biobío had been proposed, but construction wouldn’t begin for years. We were working with NGOs like Grupo de Acción por el Biobío (GABB) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), running conservation awareness trips to stop the Biobío dams, which I naively thought was possible. Finding a replacement was never a consideration.