The Futaleufú River in southern Chile has beautiful scenery and a series of challenging white-water rapids.

Several elements combine to make it an incomparable sports adventure: the breathtaking scenery, the series of formidable Class IV and V rapids, the extraordinary fishing, the hospitable climate, the cultural charms of its farm community of homestead pioneers, the campsites and hiking trails, the absence of biting insects and the unusual color and clarity of the water.

In March, I made my third trip on the Fu with Earth River Expeditions.

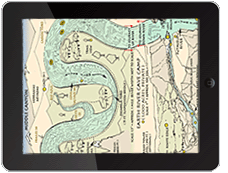

From Santiago, we flew 1,000 miles south to Puerto Montt. A three-hour bus trip on a narrow dirt road introduced us to the stunning landscapes of Andean Patagonia. At the confluence of the Fu and Azul Rivers, we donned wet suits, helmets and life jackets, and paused in a jungle clearing for a safety briefing and a seminar on paddling techniques. Class V white-water rafting is inherently risky, but with experienced guides and good safety plans, it is no more dangerous than skiing or touch football.

After a riverside lunch, we ran a series of Class III's and IV's and finished the day with a run through Mandaca, a Class V with an eight-foot drop that brought us to our first camp, Mapu Leufu. Situated between snow-capped glaciers and rugged saw-tooth mountains reminiscent of the Tetons, Mapu Leufu is a farm of broken forests, orchards and alpine meadows on a cliff overlooking the narrow Futaleufú Valley. Chattering ibis, spoonbills and plovers flocked over grazing sheep, spooked by a pair of oxen yoked to a wooden wagon delivering our gear.

Beside the oxen stood Gremilda Zapata, deftly spinning yarn. One of the remote valley's original homesteaders, Zapata has a sheep farm and spends the winter knitting gifts for rafters. She presented each of us with a woolen hat. Rafters and kayakers are welcome in the valley, where they have brought work and opportunity for the colonists.

The following morning we ran Inferno Canyon, a string of four Class V rapids in a narrow gorge that compresses the vast energy of the Fu over a three-mile stretch of ledges, holes and wave trains.

We eddied out above Inferno to scout the first rapid with a breaking hole at its entrance, followed by a wave train that could plow a raft against a hoary granite wall. At the bottom on river right, a 10-foot ledge could flip a raft. Our guide, plotted a line with four moves, which we executed to perfection. First, we dropped a tube into the breaking hole at the top, turned the raft left for a ride down the center of the wave train, charging right just in time to miss a central hole, and then sneaked in past a ledge hole on river right.

The smaller children rode horses around the rapids. As we entered Purgatory rapid, they waved to us from atop a string of sturdy palominos, hundreds of feet above the river on a narrow trail, led by Patagonian gauchos sporting sheepskin chaps trimmed with heavy fur. Between the rapids, we took in the scenery, and Barber and I fished from the bow, quickly hooking a stringer of one- to six-pound trout. On each cast, I watched big fish follow my spinner back to the boat. I've fished in most of the states, including Alaska, and in most of the provinces of Canada, and in Latin America from Costa Rica to Tierra del Fuego. But I've rarely seen a waterway with consistently large trout in such abundance, where you can pull in respectable salmonids with nearly every cast for mile after mile of river.

The Fu has a pebbled bottom, clean water, rich vegetation and an alkaline pH, conditions that are ideal for trout. Atlantic salmon, chinook and other North American imports that grow upward of 60 pounds also swim in the Fu. The small bays and pockets of still water along the Fu's banks and below each rapid almost always yield trout. Using a brass spoon and a collapsible rod, I pulled them, voracious and aggressive, from their hiding places under the branches of willows and osiers and from beneath the granite walls that rise from the banks, or, by casting to the river's center. It was pure joy to watch them following the lure in the clean water.

The next day, we ran a steady succession of rapids before making camp, bracing for the grand finale. All of our white-water encounters to that point were preparation for our final day, when we faced Terminator, a highly technical Class V that is as challenging as any rapid rafted by a commercial outfitter anywhere in the world.

After scouting the rapid from its boulder-strewn shore, we entered on river left, driving between two offset holes — an important move, because missing that line puts you on a disastrous trajectory down the rapid's unraftable center. Then we ran a series of chutes and slides through a busy boneyard of boulders and ledges.

We drove the raft powerfully through a green slot over a pillow rock dropping 10 feet from the first major ledge, then back-paddled furiously in the ledge hole to slow the raft down and allow the bow to slide left along a diagonal wave in a typewriter move. We charged right and back-paddled off a pyramid rock, then turned hard toward the center, digging to get momentum in the current, drove the boat perfectly into the final chute and eased the raft into an eddy.

"That's Terminator," our guide said, grinning. "That's so much fun."

As we sat around talking that night, another guest told me that the expedition had been transforming for him and his family.

"We've never done anything like this before," he said. "People told us we were crazy to try Class V white water, but once we got here, we felt as comfortable and safe as we do at home."

"The children loved it, and they are already planning to come back next year."