A documentary chronicling an Earth River conservation expedition down the threatened Great Whale River in Quebec. Features policymakers, environmentalists, and Cree Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come.

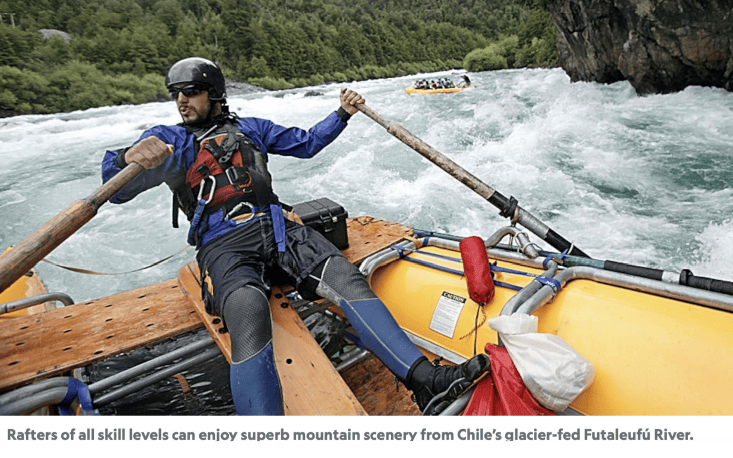

Futaleufu

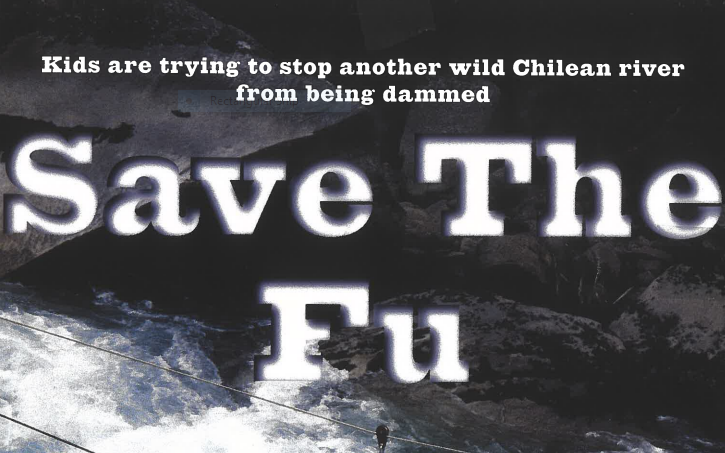

Fu Fighters

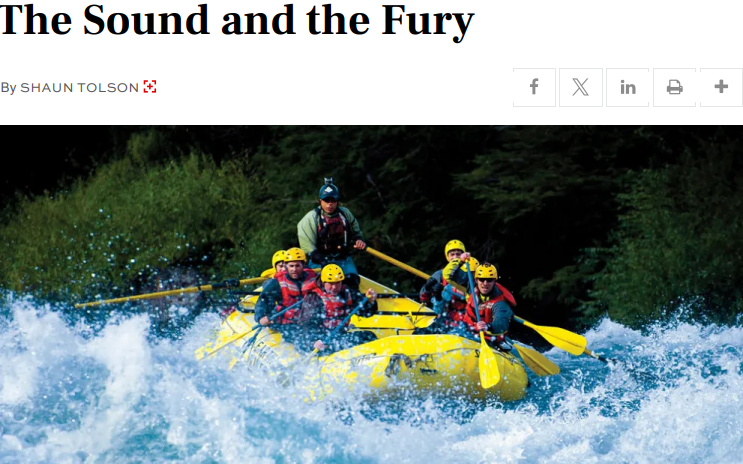

Cutting through the green, snowcapped Andes in southern Chile like a satin ribbon, the “Fu” is nirvana for paddlers. Along with mind-bending Class V rapids, the river has two unique features: On its 120-mile, 8,000-foot descent to the Pacific, the Fu’s melt-water stops in several lakes, which simultaneously warm it – at 61 degrees, it […]

Fighting the Fu

Time may be running out for adventurers who want to tackle Chile’s Futaleufu River – A 100-mile cerulean stripe that roars out of the Andes across the top of Patagonia to the Pacific. The Caribbean blue water, lush old-growth forests, Andean glaciers, and breathtaking mountain vistas belie the world’s premier white water. Here’s what it’s […]

The best Whitewater Rafting

short of measuring the size of every wave, it’s impossible to create an empirical list of the world’s best whitewater. In addition to the water itself, we looked at the quality of the company and the immeasurable awe, like how many grizzlies you might encounter along the shoreline.

Conservation

VIVA LA MAGPIE

Floating down a big North American river, the kind that flows for days with no signs of civilization. The water is black and inky, and when sunlight hits the foam, copper-colored swirls boil to the surface. Each day without fail more rapids pour off the horizon, black granite lines the banks, and thick stands of […]

Exploratories

Rapid Descent

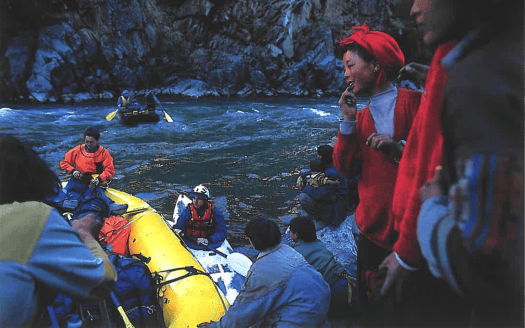

The blinds are drawn in Eric Hert’z Hotel room in downtown Kunming, China, though it’s neary noon. The forty-year-old outfitter from New York State badly needs rest. His eyes are blood shot from jet lag and stress. “I’m concerned” Eric says. “The best maps we have are 47 years old. We weren’t allowed to scout […]

The Accidental Explorer’s Guide to Patagonia

WAS ON MY WAY TO MY FAVORITE PLACE ON EARTH. I hadn’t ever been there before and wasn’t exactly sure where it was, but I knew, in the way a man knows these things, that we were drawing closer and that the place I found would be my new favorite place on Earth. Never mind […]

Rafting the “Unrunnable” Tsangpo

Since 1992, when the Chinese began admitting foreign adventurers to Tibet’s “Great Canyon,” the chasm’s white-water rivers have acquired a sinister reputation. The Yarlung Tsangpo has so far claimed the lives of two kayakers attempting first descents: Yoshitaka Takei, a japanese man who

Magpie

VIVA LA MAGPIE

Floating down a big North American river, the kind that flows for days with no signs of civilization. The water is black and inky, and when sunlight hits the foam, copper-colored swirls boil to the surface. Each day without fail more rapids pour off the horizon, black granite lines the banks, and thick stands of […]

The New Frontiers

AN ESTIMATED THREE MILLION AT LAST COUNT, the population of whitewater rafting enthusiasts in the United States has doubled in the lase ten years. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the number of whitewater rivers, which the laws of geology have pretty well fixed for the next few thousand years.

Broadcast Media & Documentaries Featuring Earth River Expeditions

1993 – TBS: “Network Earth”

Director: Barbara Pyle

1994 – Nickelodeon: “James Bay”

Host: Linda Ellerbee

Filmed during an Earth River conservation journey down the Great Whale River.

1994 – PBS: “That Money Show”

Director: Kate Reynolds

A feature highlighting Earth River Expeditions as a small, family-run adventure travel business.

1995 – ABC Sports: “Women of Adventure”

Profile: Beth Rypins, Earth River Guide

A segment filmed with Earth River’s support on the Futaleufú River in Patagonia, focusing on Earth River guide Beth Rypins.

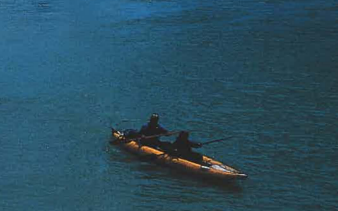

1996 – National Geographic: “Rapid Descent”

Host: Beth Rypins

Chronicles Earth River Expeditions’ first descent of Tibet’s remote Schuilo River.

1997 – ESPN/Men’s Journal Special: “Raft the Wild Futaleufú”

Director: John Barrett | Host: Don Wildman

A documentary on Earth River’s pioneering Futaleufú River trip.

2001 – Discovery & Travel Channel: “Don’t Forget Your Passport – Patagonia, Chile”

Director: Gordon Seville | Host: Karen Blaine

Explores the wild beauty of Patagonia through Earth River’s Expedition down the Futaleufu.

2014 – National Geographic Explorer: Battle for Paradise

Director: David Hamlin | Host: Boyd Matson

A conservation journey with Earth River through British Columbia’s Headwall Canyon, threatened by clear-cut logging.

Visiting Media Program

We welcome media on assignment to join us .

Please contact us to arrange your story.

We offer a selection of digital assets, including photography and b-roll footage, and story materials for editorial purposes. For permission and access to hi-res files, please contact us at info@earthriver.com Credit for the use of photos and video assets must be given to ‘Earth River Expeditions’ unless noted otherwise.

Media Materials

Story Starters for Media

Media enquiries: info@earthriver.com